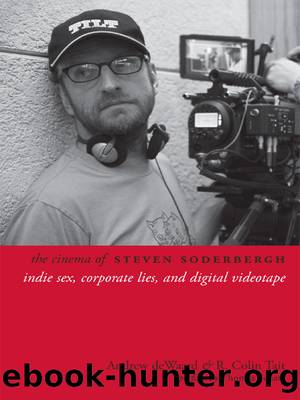

The Cinema of Steven Soderbergh by Andrew deWaard

Author:Andrew deWaard

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: PER004030, Performing Arts/Film & Video/History & Criticism, PER004010, Performing Arts/Film & Video/Direction & Production

Publisher: Columbia University Press

Published: 2013-05-06T16:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER FIVE

Returning to the Scene of the Crime: Solaris and the Psychoanalytic Detective

Earth. Even the word sounded strange to me now⦠unfamiliar. How long had I been gone? How long had I been back? Did it matter? I tried to find the rhythm of the world where I used to live. I followed the current. I was silent, attentive, I made a conscious effort to smile, nod, stand, and perform the millions of gestures that constitute life on Earth. I studied these gestures until they became reflexes again. But I was haunted by the idea that I remembered her wrong, and somehow I was wrong about everything.

Chris Kelvin, Solaris

Having considered how The Limey absorbs and aestheticises the operations of history and memory within its formal and narrative structure, and how the process of âremembering correctlyâ functions within Soderberghâs conception of schizophrenia and nostalgia, we can continue our exploration of the role of the detective in Soderberghâs oeuvre. Solaris takes the process of memory details and negotiation of personal histories one step further, not only immersing the spectator in the characterâs memories, but allowing the characters to actually interact directly with these recollections, as a result of the planet Solarisâs psychological effects on the inhabitants of the orbiting space station. In effect, both the protagonist and the viewer are required to return to the scene of the psychoanalytic crime.

Soderberghâs Solaris differs from Tarkovskyâs film (1972) as well as the original science fiction novel by Stanislaw Lem (1961), on account of its mostly psychological narrative and its expression of three separate but interrelated traumas. The first of these is on the level of character, as the protagonist Kelvin must come to terms with his wifeâs suicide by delving deeply into his own complicity with this traumatic act, a narrative arc emphasised by formal and stylistic embellishments. The second is Soderberghâs artistic trauma as he copes with the fact of his âbelatednessâ and his personal engagement with a larger canon of film history, particularly as he seeks to âremakeâ one of the classics of art cinema, while folding in the influence of another, Stanley Kubrickâs 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). The third is a negotiation of a much larger, societal trauma, a result of the production of Solaris and a release in the wake of the events of 9/11, one of the first films dealing with loss and reconciliation in the uncertain years following the attack on the world Trade Center. Thus, the mournful tones, gloomy palette, and various narratives of loss in Solaris are woven together into a complex tapestry of trauma, one that both the detective and the viewer are charged with unravelling.

Temporal and Psychological Trauma

The protagonist of Solaris is a psychologist, which foregrounds the narrativeâs concern with the unconscious and prompts the viewer and critic to a psychoanalytic reading of the film. The patient who is subjected to an intense traumatic event, as formulated by Freud and others, bears damage to their psyche and is doomed to repeat the repressed symptoms that erupt unexpectedly in everyday life.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Coloring Books for Grown-Ups | Humor |

| Movies | Performing Arts |

| Pop Culture | Puzzles & Games |

| Radio | Sheet Music & Scores |

| Television | Trivia & Fun Facts |

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(5179)

Gerald's Game by Stephen King(4654)

Dialogue by Robert McKee(4404)

The Perils of Being Moderately Famous by Soha Ali Khan(4220)

The 101 Dalmatians by Dodie Smith(3511)

Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting by Robert McKee(3469)

The Pixar Touch by David A. Price(3439)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(3309)

How Music Works by David Byrne(3270)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3073)

Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald by J. K. Rowling(3058)

Slugfest by Reed Tucker(3004)

The Mental Game of Writing: How to Overcome Obstacles, Stay Creative and Productive, and Free Your Mind for Success by James Scott Bell(2908)

4 - Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire by J.K. Rowling(2703)

Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting by Syd Field(2642)

The Complete H. P. Lovecraft Reader by H.P. Lovecraft(2563)

Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Sex, Deviance, and Drama from the Golden Age of American Cinema by Anne Helen Petersen(2524)

Wildflower by Drew Barrymore(2489)

Robin by Dave Itzkoff(2441)